Isotopic Fractionation in Geological Processes: Unraveling Nature's Subtle Selectivity

The Earth's crust whispers its history through the language of isotopes. Among the most fascinating phenomena in geochemistry is isotopic fractionation—the subtle but measurable preference of chemical reactions and physical processes for one isotope over another. This natural selectivity, often operating at the thousandth-percent level, provides scientists with a powerful tool for decoding planetary evolution, climate history, and even the origins of life.

At the heart of isotopic fractionation lies a simple truth: not all atoms of the same element behave identically. Take oxygen, for instance. The nucleus of 16O contains 8 neutrons, while 18O carries 10. This mass difference, though seemingly insignificant, influences how these isotopes participate in chemical bonds, diffuse through materials, and transition between phases. When water evaporates from the ocean surface, H216O molecules escape slightly more readily than their heavier counterparts, leaving the remaining water enriched in 18O. This process, repeated countless times across geological timescales, leaves distinct isotopic fingerprints in ice cores and carbonate sediments.

The mechanisms driving isotopic fractionation fall into two broad categories. Equilibrium fractionation occurs when isotopes distribute themselves between substances in a predictable ratio at thermodynamic equilibrium. The carbonate-water oxygen isotope thermometer, a cornerstone of paleoclimatology, relies on this principle. In contrast, kinetic fractionation arises from differences in reaction rates or diffusion speeds between isotopes. Photosynthetic organisms preferentially incorporate 12C over 13C during carbon fixation—a kinetic effect preserved in organic matter for billions of years.

Temperature serves as the grand conductor of equilibrium fractionation. The warmer a system becomes, the less discrimination occurs between isotopes. This temperature dependence transforms certain mineral pairs into precise paleothermometers. The calcium carbonate-water system, for example, exhibits a well-characterized temperature relationship that allows researchers to reconstruct ancient sea surface temperatures with remarkable precision. A 1°C change typically produces about a 0.2‰ shift in δ18O values—a small but measurable difference using modern mass spectrometers.

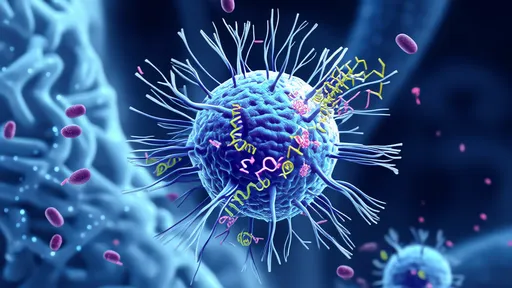

Biological processes frequently introduce dramatic isotopic fractionations that far exceed purely physical or chemical effects. The enzymatic machinery of life, evolved for efficiency rather than isotopic fidelity, often shows strong preferences for lighter isotopes. Methanogenic archaea produce methane depleted in 13C by up to 70‰ relative to their carbon source. Such extreme fractionations serve as biosignatures—chemical evidence of life's presence both in ancient Earth rocks and potentially on other worlds.

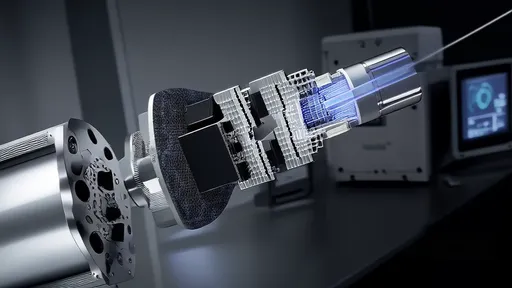

Recent advances in analytical chemistry have opened new frontiers in isotope research. Multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS) now enables precise measurement of non-traditional isotope systems like iron, copper, and even mercury. These "heavy" elements, once thought to exhibit negligible fractionation, reveal complex isotopic behaviors during redox reactions, mineral precipitation, and biological cycling. The emerging field of clumped isotope geochemistry goes further, examining how rare isotopic combinations (such as 13C-18O bonds in carbonate) provide additional constraints on temperature and formation conditions.

Isotopic studies have revolutionized our understanding of Earth's water cycle. By tracking the 2H/1H and 18O/16O ratios in precipitation, researchers can identify moisture sources, reconstruct paleo-precipitation patterns, and trace groundwater movement. The global network of isotope monitoring stations maintained by the International Atomic Energy Agency has created an invaluable database for climate studies and water resource management. In arid regions, isotopic techniques help distinguish between recharge mechanisms and quantify evaporation losses from reservoirs.

The carbon isotope record tells perhaps the most dramatic story in Earth's history. The negative δ13C excursion at the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) reveals a massive influx of light carbon into the ocean-atmosphere system, likely from methane hydrate destabilization. Similar anomalies mark other major extinction events, underscoring the intimate connection between carbon cycling and biological evolution. In Precambrian rocks, carbon isotope patterns help constrain the timing of oxygenic photosynthesis' emergence—a development that ultimately made complex life possible.

Isotopic fractionation even finds practical applications in resource exploration and environmental monitoring. Petroleum geochemists use carbon isotope signatures to correlate oil with source rocks and track reservoir filling histories. In contaminated sites, the distinct isotopic composition of pollutants can fingerprint their sources and quantify degradation rates. New techniques like compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA) allow researchers to track individual molecules through complex environmental systems.

As analytical precision improves, previously overlooked isotopic variations are coming into focus. Mass-independent fractionation (MIF), where isotopes fractionate in proportions not strictly tied to their mass differences, provides clues about atmospheric chemistry in Earth's distant past. The anomalous 17O signature in some Archean sediments suggests an oxygen-free atmosphere interacting with different UV radiation regimes. Such discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of early Earth and the conditions under which life emerged.

The study of isotopic fractionation stands at an exciting crossroads. Emerging technologies promise to reveal finer details of Earth's chemical memory, while interdisciplinary approaches connect isotopic data with genomic, mineralogical, and climate records. From the atomic scale to global biogeochemical cycles, the subtle partitioning of isotopes continues to illuminate our planet's past and present—and may one day help us recognize life's signatures beyond Earth.

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025