Ecosystem Resilience Theory: Unpacking the Mechanisms of Community Resistance to Disturbance

In the face of increasing environmental pressures—from climate change to human encroachment—the concept of ecosystem resilience has gained prominence in ecological research. At its core, resilience refers to a system's ability to absorb disturbances while maintaining its fundamental structure and function. For biological communities, this translates into a complex interplay of species interactions, genetic diversity, and adaptive capacities that collectively determine how ecosystems rebound from shocks.

The architecture of resistance within communities often begins with biodiversity itself. High species richness creates functional redundancy—multiple organisms capable of performing similar ecological roles. When a disturbance eliminates one species, others can compensate, preventing cascading failures. Tropical rainforests exemplify this principle; even after selective logging, the sheer variety of plant species allows pollinators to shift their preferences rather than collapse entirely.

Beyond species numbers, the spatial arrangement of organisms contributes significantly to resilience. Clumped distributions of foundational species—like coral colonies or oak groves—create microhabitats that shelter other organisms during disturbances. These living refuges maintain seed banks, microbial communities, and invertebrate populations that become the nucleus of recovery when conditions stabilize. The branching structures of mangroves, for instance, physically buffer storm surges while harboring juvenile fish that repopulate affected areas.

Evolutionary memory embedded within communities plays a subtle yet profound role. Populations with historical exposure to recurring disturbances—such as fire-adapted prairie grasses or flood-resistant riparian willows—develop both genetic traits and behavioral adaptations that enhance survival. This ecological "knowledge" manifests through thicker bark, dormant life stages, or even symbiotic relationships with disturbance-resistant microbes. Unlike naive ecosystems, these communities don't merely endure shocks but actively leverage them for regeneration.

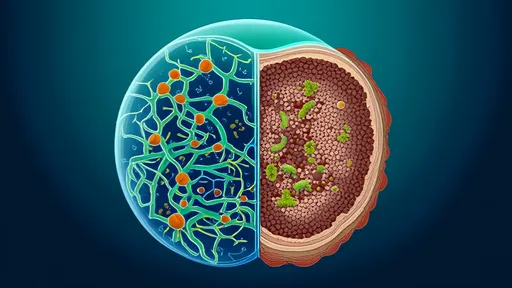

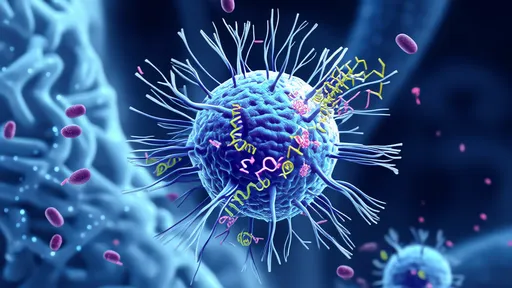

The invisible networks beneath our feet—mycorrhizal associations between fungi and plant roots—illustrate another resilience mechanism. These subterranean connections allow stressed individuals to draw resources from healthier neighbors through fungal intermediaries. During drought events, mature trees have been observed "sharing" water with saplings via these networks, effectively distributing the impact of stress across the community rather than letting vulnerable members perish.

Disturbance itself can be a sculptor of resilience, contrary to initial assumptions. Moderate-frequency disruptions—like seasonal flooding or low-intensity fires—prevent competitive dominance by any single species while maintaining habitat heterogeneity. The resulting patchwork of successional stages creates multiple recovery pathways. Pine barrens dependent on periodic burning demonstrate this principle; fire both clears canopy competitors and triggers serotinous cone opening in fire-adapted pines.

Chemical signaling adds another layer to community defense mechanisms. When herbivores attack certain plants, airborne volatile organic compounds alert neighboring individuals to ramp up defensive chemical production. This early warning system, observed in everything from cornfields to sagebrush steppes, represents a form of collective resistance where informed organisms preemptively strengthen their defenses against impending threats.

The temporal dimension of resilience reveals fascinating adaptations. Some communities employ staggered life cycles—where different species reach peak abundance at varying intervals—ensuring that no single disturbance can eliminate all representatives of a functional group. Deciduous forests achieve this through differential leaf-out times among understory plants, while marine plankton communities use diel vertical migration to distribute predation pressure.

Human influences complicate these natural resilience mechanisms in paradoxical ways. Agricultural monocultures undermine redundancy, while urban fragmentation disrupts dispersal routes essential for recolonization. Yet some anthropogenic structures—like artificial reefs or green roofs—demonstrate how designed environments can mimic natural resilience principles when properly informed by ecological theory.

Emerging research highlights the role of "keystone mutualists"—species like fig wasps or mycorrhizal fungi whose partnerships underpin entire communities. Their loss creates disproportionate vulnerability, whereas their preservation bolsters systemic resilience. Conservation efforts increasingly recognize that protecting these linchpin relationships may be more effective than focusing solely on species counts.

As climate change accelerates disturbance regimes beyond historical norms, understanding these intertwined resistance mechanisms becomes urgent. The next frontier lies in deciphering how evolutionary processes can keep pace with unprecedented change—whether through rapid adaptation, epigenetic changes, or the mobilization of long-dormant genetic variability. What remains clear is that resilience isn't a single property but a symphony of interactions honed over millennia, now facing its greatest test.

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025